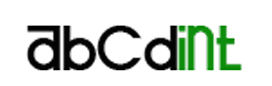

Two titans “As different as the north pole is from the south pole” is how Matisse described Picasso and himself to Gertrude Stein when they first met. He hit on a particularly dodgy paradox, for although the North and South Poles are antitheses, the icescapes surrounding them are indistinguishable.

Years Later Picasso said “When one of us dies, there will be some things that the other will never be able to talk of with anyone else.”

Their art was a unique dialogue and a wonderful match between two great Masters, like comparing white wine to red wine, Superman to Batman, Mozart to Haydn or Mickey Mouse to Donald Duck.

When Scorpio Picasso and Capricorn Matisse make an art match, they get an opportunity to not only enjoy a creative relationship and learn the value of being a pair, but also to grow and mature as individuals. These two may be wary about sharing themselves with one another at first, and this emotional caution may dampen the initial impact of this relationship. These two tend to be a bit cautious (Matisse) and pensive (Picasso), and it takes a while for them to feel comfortable with a significant other. Though they may be shy of getting involved and not the quickest to trust and share, these two Masters will discover that they can have quite a profound connection — one of friendship and deep loyalty.

Much can be learned when Picasso and Matisse get together — and the lessons they learn, while difficult at times to endure, are worth the trouble they might cause. From their stable, capable Matisse mate, Picasso can learn to bring their overheated emotions into control. Matisse must be careful, though, not to seem too emotionally shallow when leveling any criticism on their sensitive art. Detached comments can backfire with Picasso: He desires depth, intense feeling and the utmost in sincerity in all situations — most especially in art! Matisse, so busy with achieving and with how others perceive them sometimes fails to take a chance with his emotions. From Picasso, Matisse will learn the value of looking below the surface of things, the rich pleasure that can come from deeply knowing another person. Both Masters share a passion of committing to a task. If they decide a relationship is their next big goal to attain, there’s no stopping these two.

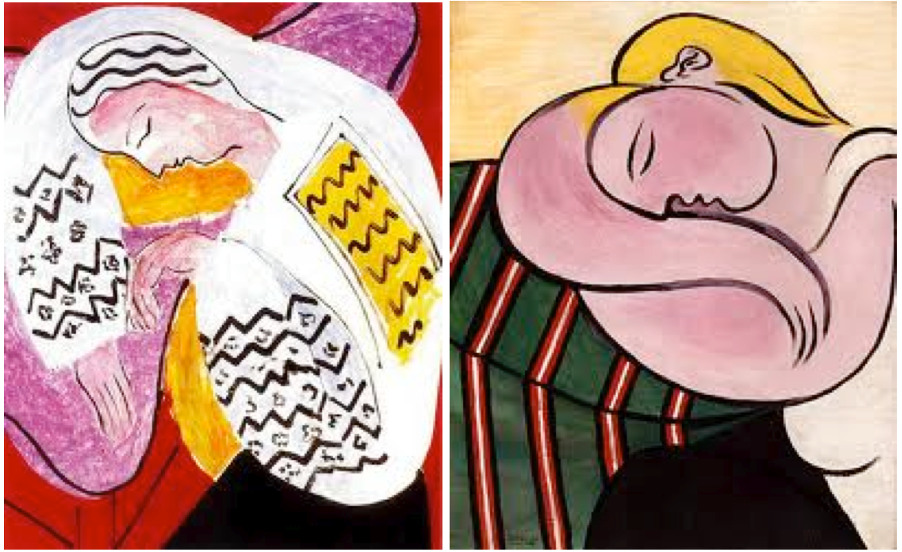

Woman In An Armchair, 1929 oil on canvas, Private Collection

The Planets Mars and Pluto rule Picasso, and the Planet Saturn rules Matisse. Mars and Pluto represent aggression, courage, sexual energy, rebirth and renewal. Saturn teaches the great lessons in life — hard work, diligence, ambition and responsibility. These three Planets can combine in the Masters to form an industrious union bound by Picasso’s fierce emotion and Matisse’s ambitious action. This is a dynamic team for business, sure, but all that achieving energy could translate well to affection and art.

Picasso is a Water Sign, and Matisse is an Earth Sign. Earth Masters are all about practical matters, about material possessions. What a good balance, then, for those of the Water element. Water Masters mold to the shape of the situation they’re in and often respond with emotion rather than logic. A match-up of Matisse’s goal-oriented stability and Picasso’s exciting mutability makes for quiet a team — whether they translate to art depends on whether art is their goal. If it is, expect success.

Picasso is a Fixed Sign, and Matisse is a Cardinal Sign. They may not seem the most romantic Signs of the Zodiac, but Matisse’s business and planning savvy could certainly be put to good use in devising elegant. If Matisse shows that much initiative, Picasso will enthusiastically follow along, excitedly, if not a bit smugly, throwing in his own ideas, too. Picasso can toss out some barbed comments under their breath or in such a sexy tone of voice that Matisse might not even notice. An art-minded Sea Goat would do well to listen closely for subtle shades and nuances in their Picasso partner’s voice and pay special attention to body language as well. Both Masters can be stubborn, and this could lead to some potential conflict. Also, Picasso falls hard, emotionally involving himself almost to the point of no return, in stark contrast to the sometimes-distant Sea Goat. Both partners must recognize this and accept it if the relationship is to be successful.

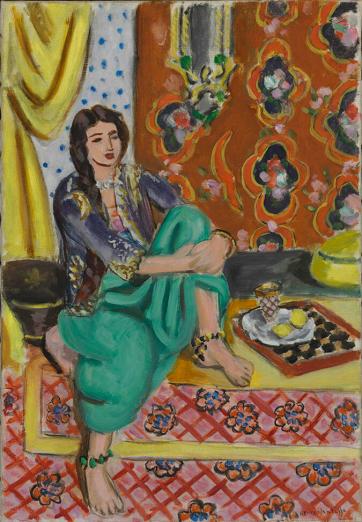

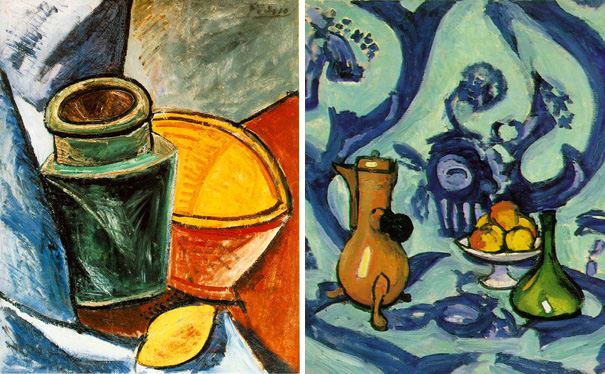

Right: Henri Matisse, Still Life with Blue Tablecloth (detail) (1909), oil on canvas, The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

What’s the best thing about the Picasso-Matisse art match? Their determination toward shared ideas and their strong devotion to one another. They can open doors to one another’s souls and show one another new ways of perceiving and feeling.